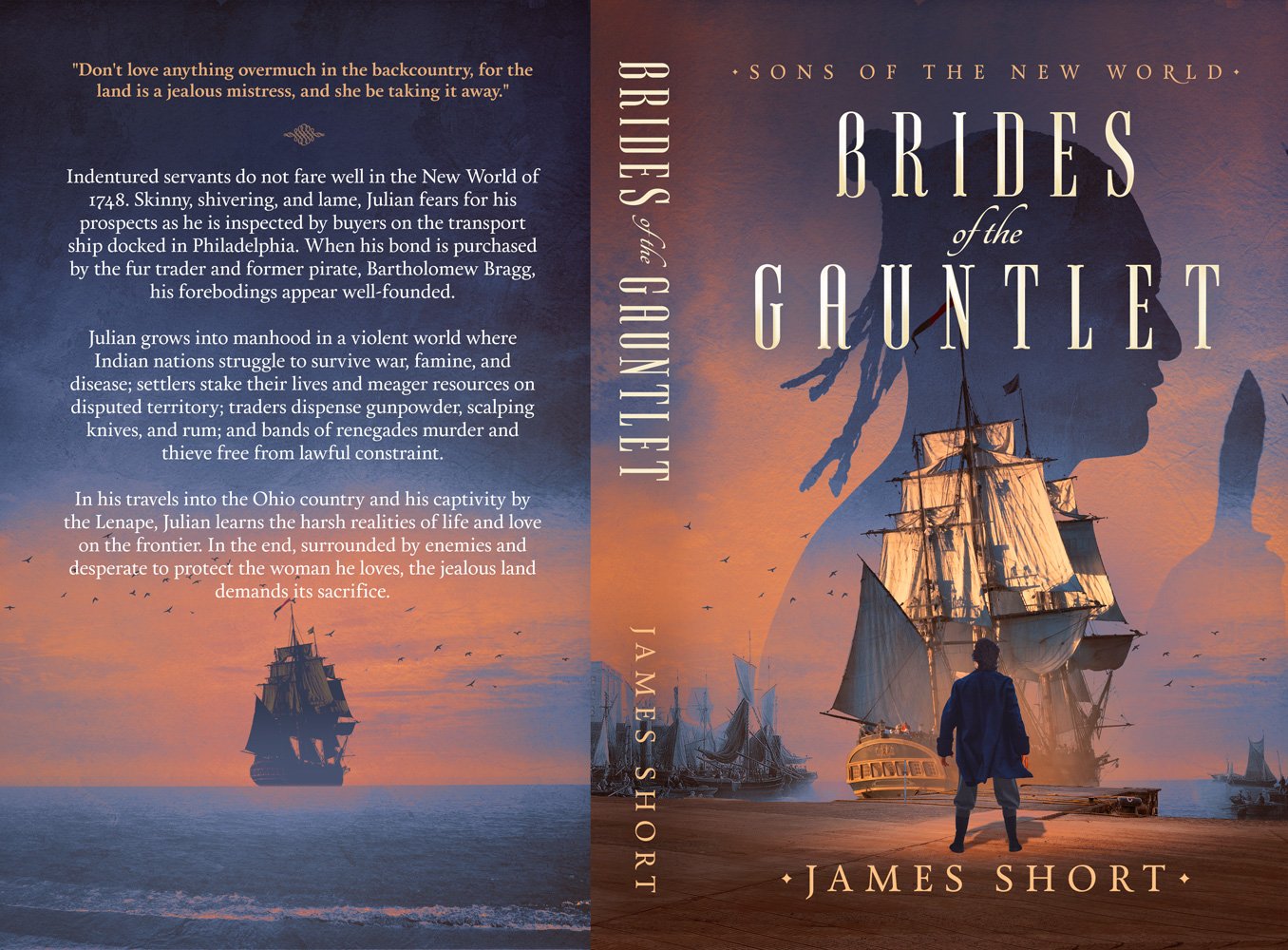

BRIDES OF THE GAUNTLET

The Rag and Bone Poor of London 1744-1746

“‘Tis a miracle again, Mistress Kate!” Mrs. Pinnock, the tenement’s self-appointed bringer of bad news and authority on neighborhood oddities, trumpeted as she barged through the door of the small apartment. The candle brightened momentarily in the rush of fresh air. A rat nibbling a flake of rotting plaster fallen from the ceiling was displaced and scurried into a gap between the floorboard and the wall.

Julian tried to disappear into the bedclothes as his mother—Mistress Kate—instinctively shielded his narrow truckle bed. After a nudging by the formidable Mrs. Pinnock who had brought what appeared to be a bowl of two-day-old porridge as an offering to their sparse larder, she stepped aside to reveal the pale wispy miracle.

“Yes, Mistress Pinnock, my poor darling’s fever broke at last.” His mother sighed the familiar sigh which comes after a wakeful night of tears. “The blisters is burst and already scabbed over, and it don’t seem he’ll be too badly pitted. Dear me, I think I wore out God’s ear praying for my little Julian. I doubt he has passed altogether two of his fourteen years free of contagion or distemper.”

“What a brave child!” Mrs. Pinnock bent down, bringing her large red face within inches of Julian’s. “Don’t he get them all—lung fever, grippe, typhus, shakes, fits, agues, fluxes, vomitings, and now smallpox?” She enumerated, not suppressing her morbid glee. “Whole blocks of humanity wiped clean by pestilence, and your Julian sweats and coughs, loses flesh until the skin covering his bones is mere parchment, yet he lives. As I say, ‘tis a miracle. Would it were his father been such a hardy weed.”

Mistress Kate briefly hung her head. Although his father was carried away by spotted fever before Julian reached the age of understanding, his presence still hovered in their shabby tenement rooms. At odd moments, out of loneliness perhaps, his mother addressed Julian as if he were her husband, her dear Mr. Stephen Asher. She would explain that although life had not turned out as they hoped, she was raising their Julian to be a good man. She was teaching him to read and do sums as her dear scholar had taught her. She feared that his long illnesses made him a solitary dreamy boy, but wasn’t it better that the London ragamuffins, ignorant of letters or morals, didn’t lure him into their unwholesome company? She prayed daily to God and to her Stephen who must be nearby in heaven for Julian’s welfare, often imploring: “Most Merciful Lord, give me wisdom to raise this boy. I am well acquainted with the needs of a man, as you from who nothing can be hidden well know, but the needs of a son are a different thing altogether.”

Instead of learning to pickpocket, steal apples, or torment cats, Julian made his own amusement fighting heroic battles in his bedclothes using sticks, pebbles, rusty buckles, and cracked buttons to serve as soldiers, and two pewter spoons to take command as generals. When he explained to his mother what he was doing, she seemed appalled, but then she said that it must be something boys did for her dear Stephen had once confided that he mastered Latin so early because his father forbade him to read about war except in the language of the Caesars.

While Mrs. Pinnock expatiated on a niece’s lip abscess, Julian turned his head away and tried futilely to lose himself in his daydreams of brave deeds. His imaginary valor, however, had lately ceased to divert him. Julian was tired of being the helpless sickly child, the over-loved burden. His uselessness was borne in on him the previous summer when a lady left for the West Indies still owing Julian’s mother the equivalent of a month’s rent for an expensive gown. After weeping tears of rage, his mother put on a bright red dress Julian had never seen before, which exposed the upper part of her breasts, and donned a cap with a peacock feather. She stood awhile trembling either from anger or from the biting cold, then declared, “Fie! Stephen’s son will not witness this. Come, dear. I’ll present you to your Aunt Clarissa. As she loved your father, so she will love you.”

His mother then changed into her usual black dress and a gray bonnet, and an hour later they were squeezed into a crowded coach trundling underneath the wooden arches of London Bridge, constructed to hold the houses that lined the bridge on either side from falling into the river. The coachman drove the horses on through the center of the city, which left Julian squashed against the window with a confused impression of broad avenues, mud-splattered gilt, a jumble of smoky chimneys, and a thousand voices hawking wares. Finally, they left the city and passed along the empty fields and woods of the countryside in the sinister gloom of twilight.

“Madam, or if you permit me to say, dear sister,” his mother addressed the pale woman in a loose satin gown seated in front of a platter of tiny fat fried songbirds. The room was the largest that Julian had ever been in except for the church sanctuary and, despite a fire in the hearth and wall hangings, the coldest. Aunt Clarissa, now a widow, had been their father’s childhood confidante and closest friend.

Aunt Clarissa frowned and adjusted her wig at the word “sister,” but otherwise did not acknowledge their presence.

Blushing, Mistress Kate forged on with her little speech pushing Julian forward. “Madam, I come in the hope that you’ll condescend to make the acquaintance of Julian, your nephew, the son of your late brother. Despite having only a poor teacher such as myself, he is accomplished with his letters and his sums. He speaks like a little gentleman. With the right encouragement and the right advantages, I’m certain he will make a fine scholar like his father.”

Julian stared fascinated as his aunt speared one of the small brown creatures with a fork then, behind the privacy of a napkin, softly crunched it. Lowering the napkin, she speared another.

“You claim this boy is a great scholar,” Aunt Clarissa said abruptly, turning her keen gaze on Julian. “I see very little of my brother Stephen in him.”

His mother’s blush deepened. “He has dear Stephen’s blue eyes and…”

“Stephen read Latin fluently by his seventh year,” Aunt Clarissa interrupted. She gestured to the tall stout bracket-faced footman. “Gunter, fetch a book from the Latin shelves of the library so we can try this young man’s ability in the language of Cicero and Virgil.”

“Madam, I never learned him Latin,” Julian’s mother said flustered.

His aunt contemplated the songbird impaled on her fork, ignoring her.

Gunter returned and set a great book before Julian.

“Read to us, dear boy, so we may be astonished at your scholarship,” his aunt said from behind her napkin.

Bending over, Julian opened the book, determined to prove himself. He took in a deep breath, and with all the will in the world to make his mother proud, started to speak: “Ah… ah… ah…” Strange words swam meaninglessly across the page. He tried sounding them out in the hope his tongue made sense of what his mind could not. “A mas reglases…” Realizing that he was failing his mother, Julian shouted his mangling of what seemed already mangled words. “A mas reglases…”

“Enough of this farce!” his aunt barked, dropping her napkin and exposing the half-chewed songbird in her mouth. “Indeed, as I suspected, you’re a slovenly stupid deceitful child. Our dear father taught us that to be charitable towards sin is to be in league with sin. Furthermore, I don’t intend to encourage this unfortunately modern trend of bastardy with patronage.”

“Please, madam. Julian is not a natural child. Stephen and I was wed in a church under the eyes of God, as properly done as any marriage in England.”

The aunt’s eyes widened with outrage. “A proper marriage? Fie! How could a woman like you pretend to a proper marriage? You snare my unworldly brother with your harlot’s wiles, then dare call it proper? Stephen would surely be alive today and a great man of learning if he had took our late father’s admonition and cast you off instead of shaming our family’s name and breaking my heart with his repugnant union to… to…the word has such a nasty taste… a whore.”

Julian’s mother bowed her head.

Julian, comprehending now that his aunt had played a trick on them, thrust the book in front of her and commanded in his high firm voice, “You read the text, madam.”

The footman Gunter spun Julian around, tweaked his nose and cuffed him on the side of the head knocking him to the floor. “Dare you show disrespect to the lady. You be bleeding brains unless you beg forgiveness.” The shadow of a large boot hovered over Julian’s head.

“Please, spare him.” His mother fell to her knees. “Julian never was a troublesome boy. He sits still at church and knows not how to say a naughty word.”

“No, Gunter, don’t trouble yourself. Violence upsets my digestion.” Aunt Clarissa stabbed the last songbird viciously and held it up with her trembling fork.

“As you wish, madam,” Gunter replied, pulling Julian up and dragging him out by the ear. His mother followed weeping.

When Gunter locked the gate behind them, Julian realized that they had made no provision for failure. Their last pennies had been spent on the coach. They were stranded in an unfamiliar country, at least twelve miles outside of London, and evening was approaching fast.

Luckily, after traipsing the first cold mile, a farmer driving a cart of cabbages took pity on them and offered a ride. Their rescuer, having liberally taken refreshment at various inns along the way started to converse with himself in different voices, claiming that by making it sound like there were more people in the cart, highwaymen would keep away. He promised to share his pot of ale with Julian and the “fancy lady” if they contributed two or three new voices to the conversation. The ale and the silliness of the exercise put them in better spirits. When the cart clattered to a stop in the vegetable market at Covent Garden, the hour was nearing midnight, and the streetlamps on the broader boulevards were mere pale blurs in the soupy mixture of smoke and fog.

After profusely thanking the farmer, Julian and his mother started out on the furtive dangerous labyrinthine journey to their fourth-story rooms in the East End. Avoiding watchmen and rakers of night-soil, they traversed thoroughfares and dark squirrelly alleys, crossed London Bridge, then delved into the muddy unpaved ways of the East End. Julian wanted to complain about his wet numb face, the loose sole of his right shoe and the aches in his calves and ankles pleading with him to rest. He knew his mother’s moods, however, and her stony demeanor signified that along with bodily discomforts, she was heartsick, and he was the cause.

Church bells struck one. Julian began to fear they were lost. Finally, the slightly fecal whiff of the tanneries indicated they were approaching the Southwark district and the tenements known generally as the rookeries and to Julian as home.

“Don’t cry, Mama. We’re almost there,” Julian whispered when he heard her gasp, not yet discerning the three men, two masked and with one disguised by a scarf, materializing out of the gloom.

“We are Mohawks,” announced a voice behind a grinning mask. “And you are a French maiden we captured and who we will use according to our savage nature.”

Julian shrank back. For sport, young gentlemen often adopted the name of that fierce New World tribe and roamed in gangs terrorizing the citizens unfortunate to be out so late.

“Come now, mademoiselle, the nicer you are with us, the gentler we’ll be with your cunny,” a frowning mask explained as he pushed Julian’s mother against a wall.

“‘Tis a shame to hide such fine bubbies,” a third man said underneath his scarf, then growled and advanced with open hands and wriggling fingers at the level of her bodice.

Julian, who had disappointed his mother once this day, wasn’t about to let it happen again. He hurled himself at the grinning mask, fists windmilling. Unfortunately, Julian was a thin wheezy child with stick-like arms and a sunken chest. The grinning-mask Mohawk laughed as the fists fell furiously and ineffectively on his buckskin waistcoat. He pushed Julian toward the frowning mask who batted him to his comrade disguised by the scarf. The Mohawks indulged in this game a minute calling him their shuttlecock. The frowning mask then lifted Julian and tossed him to the grinning mask who dropped him into a rancid puddle. Rising from the muck, Julian lowered his head to charge. A soft restraining hand fell on his shoulder.

“Loves, dearies,” a sweet voice sang out. “Why do you pester a boy and his aged mother when you might entertain yourselves with an eighteen-pence girl like me? Surely you are men of discernment. My custom house is open, and I am as fresh and clean as a rose after an April shower.”

“I see no apparent reason why the three of us don’t chive the pair of you,” the grinning mask replied in the amused tone of playful banter.

“No reason dearie, except I’ll not allow it. I have a cozy nest around the corner, and you’re all invited to share it; that is apart from the ancient crone and her little boy. La! You think you might oblige me by force? A lady like me always got her bully boys and bruisers to do her bidding lest she encounters mistreatment, don’t you know. Two of you is old friends already. Isn’t that so, Gerald and Hal? And by the morning, I expect the amusing gent with the scarf around his mug must also be. …” With great skill, she drew them in, and the fierce Mohawks were even agreeing to pay as Julian and his mother crept away.

The farmer had given them two cabbages, providing sustenance for two days, which was just enough time for his mother to find work as a seamstress in a fashionable millinery. As for Julian, he learned that day that he was neither clever nor strong. He did not see how these defects could be remedied even if he lived three lifetimes. He was fated to be insignificant; pitied and loved only by his mother, and would spend his life among the thousands of the insignificant poor of London.

Every child in London, poor or middling, worked—selling small coal or candles, black booting, pickpocketing, running errands, cleaning jakes, sweeping chimneys, collecting rags, and dozens of different apprenticeships from the common ones like smithing and coopering and tailoring to the richer sort like watchmaking and silversmithing. The poorest might even skin the carcass of a dead dog to sell its pelt, and in Julian’s tenement, two French girls earned their living chewing paper to make papier-mâché. Then there was the mysterious occupation of the prettily dressed children that involved catching the eyes of strangers, taking them by the hand and asking them if they were lonely.

Every child worked, it seemed, except for Julian. Born feverish and coughing, Julian had spent most of his life on one side or the other of a close call with death. Eleven weeks, by his mother’s reckoning, was the longest he had gone without at least an ague. Then in his thirteenth year a miracle happened: Julian managed to stay in good health through the entire winter and spring. A pale rose bloomed on his cheeks. He had grown so that his mother no longer called him, “my little twig.” The other day, after watching bull-baiting in which a terrier was tossed twenty feet into the air and caught by the alert owner, and then two women in shifts fight with wooden swords until blood was drawn from the cheek of one, he ran the whole length of Hyde Park just for the joy of running. Today, he might run it twice. At least that would give me something to do and make the day different.

Now that her dream of her son becoming a scholar was quashed, Julian’s mother, with a note of disappointment in her voice, began to suggest other suitable vocations. If he became a servant in an elegant house, he might acquire fine manners and rise to the level of footman or even valet. Glovers always made respectable livings. Much good could be said about the vocation of tanners once you became accustomed to the stench.

When Julian declared that he wanted to become a captain of a great ship, maybe even a famous pirate, or highwayman, her reaction was furious--she actually slapped him and cried, “La! That’s a foolish profession.”

“Why should I not be a great sea captain?” Julian protested, rubbing his cheek. “I want to do something brave.”

“Brave men always take another heart with them when they die, and they always die,” his mother replied bitterly. Then, caressing his stinging cheek, she told him she had made the resolution that he would become a printer’s apprentice. He could read unlike many boys of his station. His father had loved books, and she believed that Julian, if given the chance, would develop the same abiding love. With the determination of a devoted mother, she dragged him around to a dozen shops. The printers reinforced Julian’s estimation of himself.

“Such a wee pale thing, my customers might think I’m a terrible master who abuses his apprentices,” one explained. “Pray, consider Miss, that with his slender shoulders and skinny rump, your lad might be better suited to sweeping chimneys,” another suggested. After a dozen such refusals, his mother decided to wait a few months until Julian could make a healthier impression. When Julian contracted smallpox, worse to endure than the boils and the fever was the resignation in his mother’s eyes. Her darling could never be more than what he was now: the child who would always need her care.

And in his heart of hearts, to become more than the sick child seemed to Julian beyond the reach of any miracle.

The Boy Wayfarer

Julian did not remember his father, which was fortunate because if he had, he was certain he would have detested Mr. Skylar more. Mr. Skylar was definitely not what a boy with an adventurous spirit would want in a stepfather. The good man owned a haberdashery squeezed between a staymaker’s shop and a millinery where his mother had just obtained employment. He had taken to shyly walking his mother home. But a haberdasher should wear a wig big enough for his head—at least that was Julian’s opinion. Also, a man who aspired to be his father should be able to speak about other things than notions, threads, buttons, baubles, and ribbons, and he definitely shouldn’t be bowing and scraping in front of every lady or gentleman who happened to enter his shop. Furthermore, a father shouldn’t be so round that he couldn’t see his feet over his frock coat without bending.

However, Mr. Skylar was kind to Mistress Kate. He was always giving her little gifts—ribbons and fruits, once a goose to roast, and once very especially a half-finished bottle of sherry. Yesterday, to Julian’s amazement, his mother spilled four oranges from her kerchief onto their table. When he asked her whether she could marry such a man as Mr. Skylar, she protested, “He’s just a nice gentleman.” Her blush told a different story.

These were the thoughts niggling Julian as he wandered the streets of London with the objective of getting lost. For the sake of adventure, he had tried many times to lose himself in London’s backways and alleyways. Even while riding in a cart with closed eyes, he could identify by smell whether he was passing through the neighborhood of the tanneries, or the breweries, or the timber yards, or the coffee houses. Earlier that day, eager to be in the proximity of adventure, he had climbed atop a hackney-coach for a clear view of a hanging. The highwayman, who had preyed on the stagecoach travelers between London and Bristol for a half dozen years—robbing, killing, ravishing—stood on the cart before the crowd grinning unrepentantly.

“Chaplain, get down,” the highwayman loudly ordered the black-coated minister who was feebly reading psalms. The chaplain tottered, then stumbled off. “Save your prayers for them who deserve them.” The condemned criminal’s rapacious eyes then slowly surveyed the silent expectant throng. “I intend to die hard, and I give not a pig’s fart for repentance.”

A fat man in front of the crowd guffawed, then belched. This was followed by several other guffaws and sympathetic belches from the onlookers.

The highwayman nodded to the crowd as if he had expected no less from them. “You think I’m going to hell, well, what of it? Given a choice between heaven and hell, I opt for the warmer real estate. Tell me, why would the devil punish his faithful disciple? Arrah, no, he’ll give me a whole county of damned souls for my pleasure to torment. I lived a better life than all you poor sods, well worth this airy dance that no doubt will amuse you in a nonce, and when you arrive in hell—most of you is too ugly and too poor to be wanted in t’other place—I’ll be greeting you with a pitchfork, a pail of hot coals, and my peter straight as an arrow.”

Then the highwayman knelt and stretched his hand toward a group of three women holding babies. The caress of a dead murderer’s hand had special curative properties for wens and boils; and these caring mothers wanted to make sure that their suffering children received the benefits as soon as the corpse stopped twitching. The mothers squirmed and cringed in terror. The crowd hissed its disapproval.

The highwayman rocked back and forth roaring with laughter, then stood. “Bah, let’s end this. I won’t waste the little breath I have left on you poor sods; and we mustn’t keep these ladies and their brats waiting.”

After the execution, Julian set off in a new direction and found himself sauntering down a crowded narrow lane lined with shops and coffee houses. Thanks to Mr. Skylar’s unceasing commentary on his business, Julian could tell by the ribbons and buttons the women wore that the people were mostly of the middling sort—prosperous enough to imitate wealth but not so much as to fool a keen eye. Confirming this opinion, he spotted Mrs. Pinnock exiting a confectionery, clutching three paper bundles to her bodice like her last hope. She, of course, did not want to be put into the position of acknowledging her acquaintance with such a ragged specimen of humanity as Julian and looked through him, then turned in the opposite direction.

Suddenly, a loud clatter and several screams interrupted these observations. Two racing phaetons swerved around the corner. People pressed back against the shop windows and covered their faces as the phaetons tore down the cobblestones, wheel to wheel, splattering mud, the drivers red-faced and furiously whipping their horses. A hat was torn off a lady. An occupant of a sedan chair was spilled into the doorway of a Foreign Spiritous Liquor Shop. A chicken was caught by the spokes of a wheel and flung against a lamp. Dogs chased the carriages barking wildly.

Julian squeezed up against the window of a glazier’s shop between two tall young men. Julian had the youths pegged as cutpurses because their sallow complexions didn’t match their elegant attire, which helped them mingle with the crowd without suspicion. They also kept their lips tight when importuned by a proprietor of a clock shop to look closer at his wares, likely because the cutpurses feared their speech would betray their low station. They had been following an old gentleman with a fat pocket peeking out from beneath his frock coat and his servant—a giant African in bright green livery. The old gentleman and the servant were now pressed with them in the recess of a glazier shop. Julian had wondered how the cutpurses were going to get past the gentleman’s formidable guard.

Julian didn’t know which cutpurse insinuated a hand behind the small of his back and pushed. He slipped as he tried to scramble out of the way of the careening phaeton. He heard a crunch and wondered what unlucky person had fallen beneath its wheels, that is until he attempted to stand and saw the bloody strangely twisted appendage dangling on the end of his leg. He didn’t feel pain yet, but he screamed just the same. Julian then saw the look of concern on the face of the old gentleman as he bent over, his pocket now absent, and behind the kind face, craning forward, Mrs. Pinnock, her eyes wide in admiration.

When Julian woke, he found himself laid out and tied down on the rickety table in his tenement apartment. A screw-like object with bands was attached to his left calf. Further down, where his foot should have been, this red splayed thing stuck out. His mother sat on one side, all tears and caresses. A barber-surgeon squatted on a stool on the other, whistling a tune and sharpening the inside edge of a large curved knife on a whetstone. Julian attempted to speak, but in the flood of pain that came with consciousness, he only emitted pathetic whelps.

“Payment in advance, Mistress Asher. That’ll be ten shillings and a sixpence,” the barber-surgeon demanded. He had a long red nose, a great belly, and the air of a man who appreciated himself.

“I only got the five shillings saved for rent,” Mistress Kate pleaded tearfully.

The barber-surgeon slowly shook his head. “That’s enough for me to saw, but not to stanch the blood or cauterize the stump. You’ll have to perform those operations yourself, madam.”

“Only I am not knowing how,” Mistress Kate protested helplessly.

The surgeon stopped sharpening the knife. “I do not relinquish my expertise for naught for then it will be worth naught. To be honest with you, madam, if you don’t cut off the foot, your son will die a hellish death within the week from blood poisoning. If you don’t stanch the blood, then he’ll drain dry within the quarter-hour. Some opine stopping blood is easy, but give no credence to those fools. Even for accomplished surgeons like me, ‘tis touch and go, although I never lost a patient yet from bleeding out. I’m as skilled as any barber in London in the cauterization of the stump, which is where an unpracticed hand oftentimes loses the game.”

Julian’s mother began another round of weeping.

Oblivious to her tears, the surgeon continued: “The trick is to apply the boiling tar immediately to the fresh cut. Another four shillings, but well worth the expense because it makes for a smooth surface afterward. Then, there is the tuppence for the gin—mind you, superior gin from the distilleries on the river above the city, not the rag-water from the distilleries below. I might give you a break there. If after a few strokes the boy don’t faint, I’ll provide the gin at a penny a pint.”

“I promise to pay you before next Sunday.” Julian’s mother sniffled and wept.

“Aye, and I promise to perform the operation before next Monday.”

“The gentleman who will certainly lend me the money is not in town at the present, but…” Mistress Kate fell to her knees.

The barber-surgeon held up his hand indicating he had heard it all before. “I suggest Mistress Asher that you make your pleas and promises to your neighbors. If your gentleman is so trustworthy, they will have a greater acquaintance with that fact.”

“Do me the favor of waiting here a moment,” his mother said and hurried out the door. Julian wanted to tell her not to bother because he was going to die very soon, but to his shame the words wouldn’t leave his mouth.

Surprisingly, Mistress Kate quickly returned with a large woman whose presence made their room shrink and the barber-surgeon cringe. The woman’s unfamiliar face, although ugly with deep folds, was kind.

“I am Mrs. Gunn from Pennsylvania. I am visiting my sister who lives across the way. What be thy name, friend?” She addressed the barber-surgeon.

“Robert Eagleton, surgeon, ma’am.”

Mrs. Gunn smiled a warm smile. “Friend Eagleton, wouldst thou be so kind as to fetch water and clean rags. I want to examine the foot before I lend money to have it amputated.”

Eagleton hesitated. “With all due respects, Mrs. Gunn, I doubt you possess sufficient experience in these matters to render a judgment.”

Mrs. Gunn’s smile hardened. “With all due respects, friend, I have ministered to the illnesses and injuries of my family, servants, and neighbors these twenty-five years. I sewed back the hair of a scalped girl; I set the broken leg of a twenty-stone man, and coaxed breeched twins out of the belly with harm to neither mother nor babes. Thou earnest more if thou cuttest, and I do take thee for the sort that enjoys the labor of cutting.”

“It is no sin for a man to find pleasure in his profession.” Eagleton started running the whetstone down the blade again.

Julian’s mother brought a large rag and a pail of water. The folds in Mrs. Gunn’s face deepened as she contemplated Julian’s foot, which bent out sideways. Before he turned his head away, he saw her lift a loose fold of skin on the top of his foot revealing bones enmeshed in the red muscle. She took a very long time studying the mangled appendage.

“The bones broke cleanly,” she said finally. “I see all of them, and with the help of this ingenious device preventing the blood flow, I will set them. With the grace of God, dear boy, thy foot will heal. Thou will have to hobble about with a cane or crutch, but thou will have thy foot until the end of thy days. I cannot set thy ankle for ‘twill further displace the small bones, which must heal first.”

There was a clatter as Eagleton dropped his knife and started to protest that a proper lady should know her place and refrain from interfering in a man’s profession. Julian shook his head attempting to convey to the kind Quaker woman that he wanted to die.

“Open thy mouth, dear child,” Mrs. Gunn instructed, ignoring both.

When Julian finally obeyed, a wooden spoon was thrust lengthwise between his teeth.

“Now, bite down, dear.”

The last thing Julian remembered after his teeth clamped down was Mrs. Gunn bending over his foot holding a darning needle in one hand and pliers for pulling teeth in the other.

Over the following weeks, Mrs. Gunn visited daily to inspect the progress of what she called “the mending.” Julian wasn’t certain that not chopping off his foot was the right decision. He doubted that the purplish, swollen thing at the end of his left leg could ever be serviceable, and in any event, the outward twist of his ankle meant that throughout his life he would have to shuffle sideways with the foot. Mrs. Gunn made him a gift of a crutch before she left for Pennsylvania.

“Thy foot won’t please the eye, but ‘twill serve thee better than a peg,” she smoothing his hair. “I do so miss my sons. They would make good brothers to thee, and thou, I dare say, would also make a good brother. Come visit us when thou comest to the age of manhood. Come, I will give thee a wagon and thou will carry goods from farm to market.”

When Mr. Skylar returned, he demanded that his Katy and Julian move to better accommodations. He declared that he’d bet his haberdashery their tenement like two others owned by the same landlord would collapse before the year was out. With only one flight of stairs to climb to the second-story apartment and a window that opened out onto a courtyard, the new accommodations were vastly superior to the old. Julian had never experienced the luxury of a window before, nor a courtyard that was swept daily, and a week could pass without spying a rat in the hallway.

Julian’s foot healed slowly unlike his broken dreams which seemed beyond repair. Perhaps it had been childish to want to be a pirate, but it wasn’t childish to desire to cut a figure in the world, become a man admired, not pitied as a cripple. Making matters worse, Mr. Skylar started advocating apprenticeship in his shop. “Every lad’s head is filled with notions, Kate, and little Julian’s head got more than most for he spends so much time with nothing to do but think about what’s in his head. ‘Tis well known too much cogitation unbalances the humors and causes melancholia. As you no doubt can conclude from my example, there are few better enterprises in the world than that of being a proprietor of a haberdashery. A woman will pay her last sixpence on a spool of gold thread.”

Mr. Skylar visited his Katy every day now. Katy cooked for him, brushed his breeches, polished his shoes, and stood approvingly beside him when he admired himself in the mirror, and if he sneezed, inquired after his health with genuine concern. She even prevailed on him to buy a wig that fit his head.

Unlike his many illnesses where his body rebounded with no effort of will, Julian had to force himself to walk again. For a month, he hobbled around the room with the crutch, then afterward with a cane—the rap of the wood tip, the soft step of the injured foot, and the firmer resonance of his good foot making a clip-clunk-clop sound. Thus, he tottered back and forth, weeping and biting his knuckles. A group of boys threw pebbles at him when he first appeared outside hobbling with the cane, saying it was pennies for the cripple. Julian threw the cane at them vowing never to pick it up again and, choking with pain, lurched back inside and up the staircase to their tenement apartment, his stride becoming an uneven step, slide... step, slide…

A week later, he stepped, slid… stepped down the stairs to the street and then to the end of the block where a little girl sold apples from a wheelbarrow in front of a dram shop. When he returned, his face sheathed with sweat and tears, he took two bites out of the hard-won apple and promptly vomited. Repeating the trip the next morning, Julian walked five paces beyond the apple girl—step, oh-God-have-mercy-on-my-foot slide… step—and then turned around. Every evening, Julian resolved to go easier on himself the following day, but each morning, he repeated the ordeal lured by the belief that if he just dragged himself far enough, he might encounter something new and interesting. Julian tried to explain this restlessness to his mother and Mr. Skylar, but it didn’t make sense to them. Mr. Skylar kept reminding him that as a haberdasher he could sit on a stool between the times attending to customers.

“Every boy dreams,” Mr. Skylar lectured, “only dreams are just airy fables that put not a penny in the purse nor a morsel in the stomach.”

While Mr. Skylar delivered such homilies, Julian either glared at the smug prig until he shut up or he stared at the door abstractedly, imagining running the length of Hyde Park as he had once done. When Julian finally proclaimed that he’d rather be a beggar than haberdasher, for the second time in his life his mother slapped him. After that, Julian forced himself on longer walks, gimping along the most dangerous streets on dark evenings, daring—maybe even hoping for—a footpad to rob him or stab him. Better than becoming Mr. Skylar, he told himself.

Being a naturally timid man, Mr. Skylar’s courtship of Julian’s mother progressed slowly. Two years after the accident, Julian woke up in the middle of the night to the sound of two people snoring. He lit a candle and walked into their front room. His mother and Mr. Skylar had fallen asleep side by side on a small divan. Julian was certain Mr. Skylar had never done anything improper with his Katy. The haberdasher was a fool and pompous, but he was also kind and considerate to a rare degree. He never treated his Katy less than a lady. Julian suddenly realized that his disdain for Mr. Skylar was in truth jealousy. He had always owned the entirety of his mother’s affection. Julian was certain he could still reclaim it. By becoming the whiny sick little boy again, he could drive Mr. Skylar forever out of his mother’s life.

He fought off an impulse to go back to his room and cry out, pretending his foot was causing unbearable pain. He fought off the desire to wake them and amuse himself with their embarrassment. Instead, he took a scrap of purple-stained sugar paper and wrote with a dull pencil:

“Dearest Mother,

Remember the Quaker woman who was so kind to us and offered me a wagon so I might carry goods from her farm to the market in Pennsylvania. I decided to accept her offer. I am not suited to be a haberdasher although it’s an admirable profession. I will write to you as often as I can. I hold the greatest respect for Mr. Skylar. May he continue to treat you with the goodness and kindness you so deserve.

Your Loving Son,

Julian”

Julian kissed his mother on the forehead and put the note in her lap.

It was late October, and the chill sank deep into his bones as he stepped slid down the dark streets toward the docks. Julian realized that he had forgotten his overcoat. Returning to the apartment where his mother and Mr. Skylar leaned companionably against each other asleep on the divan, however, seemed as impossible as going back to yesterday.

Passage

A boy in his tenement nicknamed The Governor explained how it was done. The Governor boasted he could out-drink, out-whore, and out-swear any sailor, and had never lost a game of chance, and at the age of sixteen had acquired all the knowledge necessary for getting ahead in the world. When Julian confessed that he wanted a life of adventure, The Governor explained, “‘Tis simple, lad.” He called all those younger than him ‘lad.’ “Go down to them docks ‘n carry yerself aboard one of them great ships, ‘n exercise yer knuckles on this or that captain’s door ‘n say you wants passage to them colonies. The captain shake yer ‘and you puts yer mark on paper, ‘n that’s that. You ‘ave a contract in the eyes of God ‘n King ‘n off to them colonies, off to the land of milk ‘n ‘oney ‘n bloodthirsty savages you goes. I might done it myself, ‘cept an old gypsy told me I be fortune’s pet, ‘n I no want to upset ‘er by not being around when she come fer me.”

Near the docks, Julian asked a dozen different sailors in various stages of inebriation where he could sign on as an indentured servant to the colonies. Several different boats were pointed out, but Julian always lost his nerve as soon as he set foot on the gangplank. He had given this enterprise up as another failure and was wondering whether he had time to creep back to his apartment and steal the note off his mother’s lap, when a large hand clamped down on his shoulder and a hollow voice intoned, “Come with me, lad. I’ll serve as your agent.”

This self-proclaimed agent—an old sailor with long arms, short legs, and one good eye—dragged Julian to a squat tub with two masts, pulled him up a gangplank, and banged on the door below the quarterdeck. The reply wasn’t recognizable, but his “agent” apparently took it as an invitation to enter and propelled Julian forward. Julian stumbled into a desk behind which sat a scowling man with whiskers that stood straight out and eyes that might have belonged to a demon. Julian supposed, correctly as it turned out, that this was the captain.

The old tar began humbly, “Captain Broom, sir, my son here desires passage to the colonies to make his own way in the world. He is a hard worker, and I am regretting the loss of him, only there’s no holding back young blood when it gets a mind to do a thing.”

“Is this man your father, lad?” Captain Broom asked Julian after the merest disdainful glance.

Julian moved his head in a circle, not wanting to lie, but catching on that a lie was necessary.

“I take it your wobbling noggin means he can sign for you.” Broom studied Julian like an insect in his soup. “What’s your name, lad?”

“Julian, good sir.”

The captain shook his head. “What sort of work can you do, Julian?”

“Farm work,” his agent interjected.

Julian nodded slightly thinking that the less he nodded the less of a lie he would be telling.

“Balderdash! Show me your hands,” Broom demanded.

Julian stretched out his hands.

The captain snorted in disbelief. “Your hands are softer than the hands of my five-year-old niece. You never have done a day of hard labor in your life, boy. On the docks in Philadelphia the first sold off are strong-backed stout-hearted lads who think nothing of pulling out a dozen tree stumps before noon, then taking in harness the plow the balance of the day. Have you ever seen a tree stump, boy?”

“I wish to try my fortune in the colonies, sir,” Julian quaveringly asserted.

“You wish?” The captain’s eyes drilled into Julian. “Fie on wishes, lad. I wish I weren’t obliged to sail this spongy bark through stormy seas with a crew of disgruntled Yorkshiremen to the damn colonies so miserable souls can condemn themselves to further misery. The question is, boy, if this rascally impostor signs for you and I take you, how much with your narrow shoulders, sunken chest, blotched complexion, and broomstick arms you fetch on the docks in Philadelphia? And what’s wrong with that foot that you dragged in after you like ‘twas an unwanted relation? It sticks out oddly.”

“I broke it, sir.” Julian tried to hide his bad foot behind his good.

“Call me Captain,” Broom corrected and grimaced.

“Captain, sir. I broke it in a farming accident. A tree stump fell on it.”

His agent pinched him hard in the ribs and said, “He meant to say a horse trod on it, captain.”

“How old are you, boy?” Broom asked.

“I reached fifteen last April, captain,” Julian replied with relief that for once he was speaking the truth.

The captain shook his head. “No one will buy your indenture to work their land. I doubt I could give you away. Have you special skills? Don’t include lying. You’re as poor a liar as ever arose out of the riffraff of London.”

“I can read and make my letters and have a fair head for my sums, sir, captain, I mean,” Julian replied hopefully.

“I’m overjoyed to find out you’re not a total disgrace to the English nation. So why do you think anybody will give you bed and board for seven years, even if you have your sums and letters?”

“A Quaker lady promised she will supply me with a wagon to drive her goods to the market if I visit her,” Julian answered, again glad to muster more than a figment of truth. “She said I won’t be required to walk much if I am driving my wagon all the time.”

“Hmm,” The captain wrinkled his brow, seeming interested. “What is the name of the Quaker woman?”

“I cannot recall her name,” Julian answered. “Only she said she lived in Pennsylvania.”

“Then how am I to contact her? Pennsylvania can swallow England whole and still have room leftover to digest Wales, Scotland, and Ireland. And Quakers there are as thick as fleas on an old dog.” The captain now addressed the man who claimed Julian’s paternity. “If we mark his age down as twelve, which by his looks nobody would question, a buyer might see an advantage to a nine-year indenture instead of seven. How old is your son?”

“Aye, captain, my son tends to exaggerate his age. He is twelve this March,” The old tar replied promptly.

“Fair enough,” The captain replied.

Julian opened his mouth to protest.

The captain didn’t let him speak. “Don’t tell me this red-nosed baboon isn’t your father after you swore he was. I’m captain, which is to say king, judge, and executioner on this boat, and the punishment for lying to a captain is a hundred lashes, and there’s not enough flesh on your bones for fifty. I’m not promising aught. We might squeeze one more below. Get your arse on deck in the meantime. We sail tomorrow morning. If better prospects fail to show before then, you got a berth.” The captain paid the agent a thruppence, muttering as an afterthought: “Usually, I lose a fifth of the human cargo—maybe he dies instead of a more promising prospect.”

Julian spent the first hour pacing the deck, wishing mightily for his overcoat. When the ache in his foot became unbearable, he curled up next to a coil of rope. He didn’t believe sleep possible with the chill, his throbbing foot, and all the new sounds and the unfamiliar shapes surrounding him. Worse, regret began to gnaw at him. Why not resign himself to the respectable trade of haberdashery? Mr. Skylar would treat him like a son. Mr. Skylar earned a good living, and more than a few of his mother’s friends had complimented her on how lucky she was to have snagged such a fine suitor. Julian couldn’t see anything particularly fine about the man, except, perhaps, his appreciation for his Katy.

Julian began to feel ashamed that he was already yearning for his mother and miffed he had not anticipated this engulfing sadness. For near sixteen years, he had slept under the same roof as her. She had the kindest face imaginable, broad and handsome. Until Mr. Skylar intruded into their life, she had often spoken about her Stephen, his real father, with reverence. “A great scholar who read and wrote in Latin and Greek, a good virtuous man who never suffered a door closed in his face.” Then she would weep and admonish Julian, “He was a foolish fearless man. Julian, I beg you, never be a foolish fearless man.”

Julian failed to understand how a schoolmaster for the children of artisans, merchants, and others of the middling sort could be foolish and fearless. Whenever his mother shared a recollection of her dear Stephen, his father appeared as an exceptionally kind and mild-mannered man. His students loved him and never played tricks on him although they might have easily because of his weak eyesight. She claimed that he had never caned a child. He died of a fever caught from one of his pupils. The boy’s parents were too frightened of the contagion to tend to their son. Not Stephen. He spoon-fed the child hot broth, changed the soiled linen, cleaned him, read to him. The boy recovered.

Eventually, fatigue won out over the discomfort and the vast feeling of regret, and Julian fell asleep, his head resting uneasily on the coiled rope.

It must have been several hours later when an oath and a kick woke Julian. Rough hands pulled him up, and he groggily followed the shadowy sailor down three ladders into a low, dank, and gloomy space that his guide called steerage.

“This way, this way,” voices beckoned and hands reached out, directing Julian forward until he stumbled against a curving barrier.

“There you be. Yer the lucky soul getting the coffin berth,” his guide gruffly remarked.

“Where?” Julian asked, glancing around. The oil lamp swinging from a low ceiling dimly illuminated a long row of double-stacked pallets. Each pallet accommodated three to five people—strangers or families. Buckets were tied to each upright post, their fetid odor making it plain that this was where the steerage passengers relieved themselves. It seemed doubtful the occupants of the berths would be inclined to divide their meager pallet space yet again to welcome him.

“That be your place.” The sailor directed Julian to a plank slightly larger than a tray, attenuated at one end because of the curve of the ship’s bow. “You piss in their bucket. If they not approve, piss on them. You’re just the right size—not a hair’s width to spare. The captain sure has a good eye for packing them in.”

With difficulty, Julian fitted himself onto the plank. The wood oozed rot. The sea sloshed eight oaken inches away from his ear. He tried turning, but the space was so cramped that he couldn’t do so without falling out. A cheery voice in the gloom answered his question: “Make yerself comfy, lad, that be your home and hearth for the next nine weeks if winds blow fair, fifteen, if foul.”

This was simply too much. Julian rolled off the berth, stood, straightened, and steadying himself against the upright beams dividing the pallets, started toward the hatchway.

“Where do you think you’re going?” inquired an unidentifiable woman from the shadowy depths of steerage.

“Back,” Julian proclaimed. “I changed my mind.”

“Back where?” The voice gurgled with suppressed hilarity.

“To my mother.” Julian didn’t care how childish he sounded.

Several laughed. “Sprouted fins and a tail, have you?” His interlocutor continued.

“What?”

“Or wings? They might serve. What a chuckleheaded darling you are. Can’t you feel the ship moving? Swimming or flying be the only way home.” The speaker obviously relished Julian’s mortification.

Julian crawled back onto his small plank. He fell asleep before he could decide whether to rage or grieve.

A hundred and fifty people—a third of them women and children—were stuffed into the steerage of the forward hull, like bodies in catacombs. Two hundred occupied another compartment in the steerage aft. Dimly lit by swinging lanterns, the steerage was a cold, swampy, lice-infested, wooden cave. On the second day the rolling seas caused general seasickness, Julian and a few others excepted. The odors of human waste, vomit, and unwashed sick bodies thickened the air. There was never not a child crying, a consumptive coughing his lungs inside out, a man cursing, a nauseated individual groaning or voiding the contents of his gut. Julian decided that any description of hell that left out vomit wasn’t wholly accurate. The pregnant women and the newborns fared worse. One of each died the fourth day; and after the vulnerable were culled from the emigrants, the loss of healthier passengers unerringly maintained a high mortality rate for the rest of the voyage.

On the eighth day, Julian made enemies of the Lyle brothers, two sharp shrew-like boys whose greatest pleasure was the torment of weaker creatures. Like Julian, they were immune to seasickness. The second day out, the brothers caught a rat and cut off its legs on one side. They giggled as the rat struggled to escape, but kept going in circles because its brain wasn’t able to comprehend the missing limbs. Not quite satisfied with the diversion this cruelty provided, they tortured the creature for a whole day with a penny knife until they lay on their pallet shaking with laughter. Several passengers protested, but the brothers had this odd stare, their tiny eyes glinting on either side of a deep furrow that conveyed the message that they didn’t see much difference between you and a rat.

The brothers dearly missed their gin. By the sixth day, they had exhausted their farthings purchasing grog from the sailors. After trying various wheedling scams with indifferent results, they concocted a plan to replenish their funds by selling the sexual favors of a girl in steerage. From the brothers’ conversation, Julian gathered that Abigail was pretty, unaccompanied, and innocent. She had been a dressmaker’s apprentice, but the dressmaker died, and so she had indentured herself to a dressmaker in Philadelphia. She shared a pallet with a Palatine couple and their baby. To avoid the frequent scoldings of the jealous frau, Abigail took to sitting on the floor near the hatch hoping for a breath of fresh sea air. The brothers planned to lure her to the bottom deck to see newborn kittens. For a discount on Abigail’s sexual favors, the sailmaker provided a piece of canvas that would serve as the bed amid the barrels and casks that made up the ballast. The brothers debated whether to pay the girl a halfpenny for her trouble but eventually decided that would be immoral because, “She might take on the unwholesome habit of charging for pricks.”

Julian only had the blurriest notion of the facts of life and didn’t quite catch on to what the brothers intended. With his cramped berth and throbbing foot, he had enough misery himself to be overly concerned about a girl who had no thought for him. However, as the brothers became more explicit in their whispered fantasies of Abigail’s deflowering, Julian’s conscience began to nudge at him. With an effort, he resigned himself to suffer his troublesome conscience and leave Abigail to her fate, which couldn’t be so bad—after all, she wasn’t a rat.

After the brothers commiserated with Julian when the hour of the deflowering had come because the lack of a sixpence kept him from joining the fun, they sidled over to Abigail’s pallet. A moment later, Julian heard them whispering to her about kittens in the cargo hold. The poor girl issued a mew of assent. Two dead bodies in gunny sacks temporarily blocked the short passageway to the hold, so the three of them passed by Julian. This was the first time Julian had more than glimpsed Abigail. He had somehow imagined the shadowy figure by the hatchway as a hale and hearty girl, well able to endure the handling of rough men. The person clutching a dirty blanket to her gown as she was led to her deflowering, now seemed more child than woman. Her large slightly rheumy blue eyes were clouded with uncertainty, and her trembling lips were as vulnerable as an open wound. Five minutes later, four sailors discreetly slipped down the hatchway into the hold.

In the mental wrestling match, conscience bested Julian’s resolve to not interfere. Hobbling over to Abigail’s berth, he blurted out the brothers’ intentions. The Palatine family stared at him blankly. The rest within earshot were too oppressed by their own miseries to be much interested in Abigail’s plight with one exception.

Mary Winn was a washerwoman in her late twenties. She had bright red hair, the forearms of a pugilist, and shoulders as broad as any hauler and hewer of wood.

“Just as I suspicioned,” Mary Winn muttered as she extracted her square frame from her berth. She flexed her hands and growled, “Poor lads.” Julian feared that Mary didn’t comprehend the situation and began to explain again how many men might be involved. Mary Winn brushed him aside. He followed her to the hatch leading to the cargo hold and stared hopelessly as she descended, grasping in her teeth a marlinspike she had somehow acquired along the way.

In no time, Mary Winn located the lair. The battle was unseen, although not unheard. “The filthy bitch punctured my bum!” “Let go! Let go! Oh, bloody Lord, I’ll never piss again!”

Mary Winn’s husky contralto rose above the commotion. “I’ll unman ye all!” The sailors came scrambling up from the hold, clutching their gashes and bruises and spitting out broken teeth.

“Run, run, run for your lives, she’s bedlam in skirts!” yelled another to Julian through a bloodied mouth as he emerged. Mary Winn reappeared supporting the quivering Abigail who now wore a sailor’s shirt in-between the blanket and the gown. The male part of the steerage gave the pair plenty of space. Unfortunately, the Lyle brothers were agile enough to escape disabling injury. When Julian returned to his plank, the brothers, with an infallible instinct for the informer, fastened their malicious, unforgiving eyes on him.